Screenshots

are like Wellbutrin.

One of my rules of thumb when writing one of these analogies is that I don’t want anything to immediately come to mind for the reader when they see the two things I am comparing. When someone reads the title I want them to have no idea what these two things could possibly have to do with one another—or, as second best, I want them to imagine something totally incorrect. (Sometimes I go too far with this and can’t remember what the resemblance actually is after I’ve promised it to you guys—I’ve had a few close calls!)

So I’ll start this piece by explaining that the thing that screenshots and Wellbutrin have in common is not that they boost my mood. In fact, I can confidently say that screenshots do not boost my mood. When I scroll through my photos app, it doesn’t look like an accumulation of picturesque moments from my daily life: it’s a tessellation of text in dark mode and text in light mode, memes, a picture of a tree, a picture of a book cover I wanted to save for later, a picture of a sign I wanted to save for later. A sleeping cat. A headline I meant to send to someone but forgot to.

It does make me think wistfully of the time before my screenshot addiction, when the screenshot function certainly existed but (probably held back by the phone storage requirements of the 2010s) I didn’t use it to build my own personal internet archive. When I think back to my college camera rolls they are more photographic: pictures of trees (a constant), pictures of my friends goofing off, my siblings on the weekends, sunrises over the lake. My pictures of text were usually pictures of books that I was reading.

My screenshot-ridden camera roll simply tells the uncomfortable truth about my daily life nowadays, much of which is spent online or on a screen. While working yesterday I found myself taking screenshots of an AI transcription program’s attempts to render the name of a priest called “Don Giussani”:

Many of my screenshots are like this—an attempt to capture a particularly funny private moment, one that is difficult to describe. Sometimes I will send them to my best friends, and sometimes I will save them for myself, like the little jokes I write into my academic papers so I don’t get bored. There’s a file on my computer named “chaotic dissertation moments” that is 100% screenshots. Here’s one:

Ever since we all became tied to our devices, some part of me has envisioned the life of the biographer of the future—some real person or AI who will weave our lives together from the digital threads we left behind. Once I got used to time-stamped video and text messages and emails, I realized someone could someday go through everyone’s digital lives like they are putting together impossibly complex jigsaw puzzles: ah yes, on October 21, 2019 she emailed a professor, then she made a grocery list on her Notes app, then she and her best friend spent 20 minutes on a goofy riff about Jordan Peterson…

The fact is that no one cares enough to do that, including myself. But I still want to grasp for permanence, to capture the moment that a Pinterest quote graphic left me embarrassingly moved or someone on Twitter perfectly described the present moment. Part of this might be the fear of dementia, dated from watching The Notebook at an impressionable age. I want to know that one day, if I forget everything, I will have it with me to read and reread. The Internet is a constantly-moving river: things are left behind and deleted all the time. But, floating in that river, I find things that I love and I don’t want to lose them. And they go into my 27 gigabytes of iCloud storage.

There’s this feeling when you are depressed that you are missing something. Missing some part of yourself—missing your life, perhaps. The many mental health medications of our time promise to change that, to return you to some previous version of yourself, restore your presence in the world to what it was before. As the Midwest descends into darkness every fall, I feel my experience of the world changing. Things seem less hopeful, more mundane, more boring. A fear creeps up: the fear that I am going to miss something, an indelible moment, a tiny detail, a very specific feeling. Something that I won’t even know I am missing.

Here I’m not going to go directly into any personal experience with antidepressants. Wellbutrin is a stand-in for anything of its kind—the medications that promise to get our brains and our emotions right. About 24 percent of American women are being treated for depression, and it’s the journey of these medications that fascinates me.

These medications can be a truly wonderful thing. They can lift fears and dark moods that make life difficult to live. But of course, as anyone who has experimented with antidepressants knows, this seeming solution can raise another fear: that somehow they will deaden our experience, silence our emotional lives, lull us into a lack of consciousness. For some people, they do—or they seem to. But what actually is a normal amount of consciousness? What is a normal amount of fear? What is a normal amount of sadness? To me, that’s the inherent paradox of medications like these. The fact is that, whether you take Wellbutrin or not, there’s no way to promise yourself that you won’t miss the ephemeral moment. You can miss the moment medicated; you can miss it unmedicated. The moment will still require attention.

There’s a promise that SSRIs and other medications can try to make to us: that they can provide us with the experience of the world that a “normal” person has or that we “normally” have, that they can hone a few lenses in our vision of the universe and restore them to perfect 20/20 vision. For many, they are life-saving and indispensable. But there is no normal. That perfect perspective does not exist.

The fact is that, no matter how many screenshots I take, I can’t recapture the particular moment that moved me. Not perfectly. I won’t ever reconstruct my experience, build out a perfect model of my digital day or my digital life. That version of my life is still in the stream of time, and can’t be extricated any more than my “outside life” can be. If I fail, in the moment, to attend to the moment, it will be lost. There’s no way for me to hone my particular experience of the world into perfect awareness—no way other than looking.

We talk, in the mental health age, like we can refine our vision of reality to such an extent that we will have an objective view of all things. Our emotions will be exactly proportional to what happens. We will see the world precisely as it is. SSRIs are meant to help with this. So are meditation, and mindfulness, and gratitude, and cognitive behavioral therapy. All of these may enrich experience. But none of them “fixes it.” None of them are a solution for one of the fundamental frustrations of the human experience: that it is a constantly-moving kaleidoscope. If we live our lives in the fear that we are going to miss irreplaceable moments, we may miss them for that very reason, just as we are sometimes going to miss them anyway. All we can do is take a moment to appreciate when something extraordinary crosses our path, and then move on.

But I don’t think it’s possible to miss the experience of being who we are in time. We can’t escape it.

Come back in two weeks: for a patron-only post on why podcasts are like puppies. Promises to be particularly personal and passionate.

Found a pretty solid: nonpartisan news source.

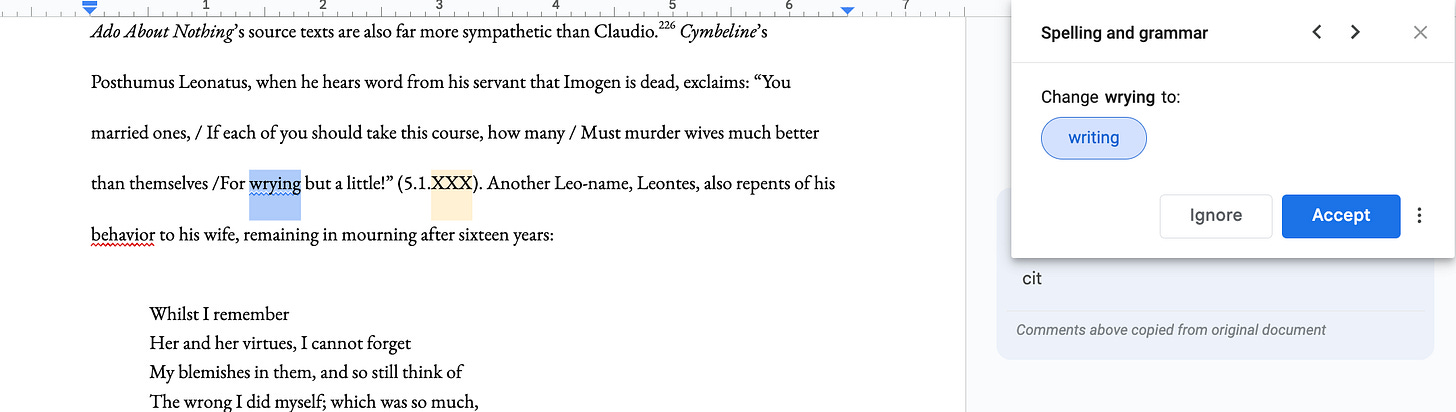

My camera roll does still have some photos on it: