There’s a charming story from when I was about four years old. My parents had given me a little cassette player with Bible stories and songs for children, and I was completely glued to it, listening to it wherever I went. Apparently my mom went to take away the cassette player and I said “how will I know how to live?”

I think about this story fairly frequently, partly because I still want to know how to live, and partly because it’s pretty transparent to me that there isn’t that much of a difference between my four-year-old addiction to the Word and Song Bible and my twenty-eight-year-old addiction to cultural commentary podcasts. What I said when I was four was true; it was also an excuse to keep listening to my cassette player. But what makes that story charming is, in my opinion, the cassette player.

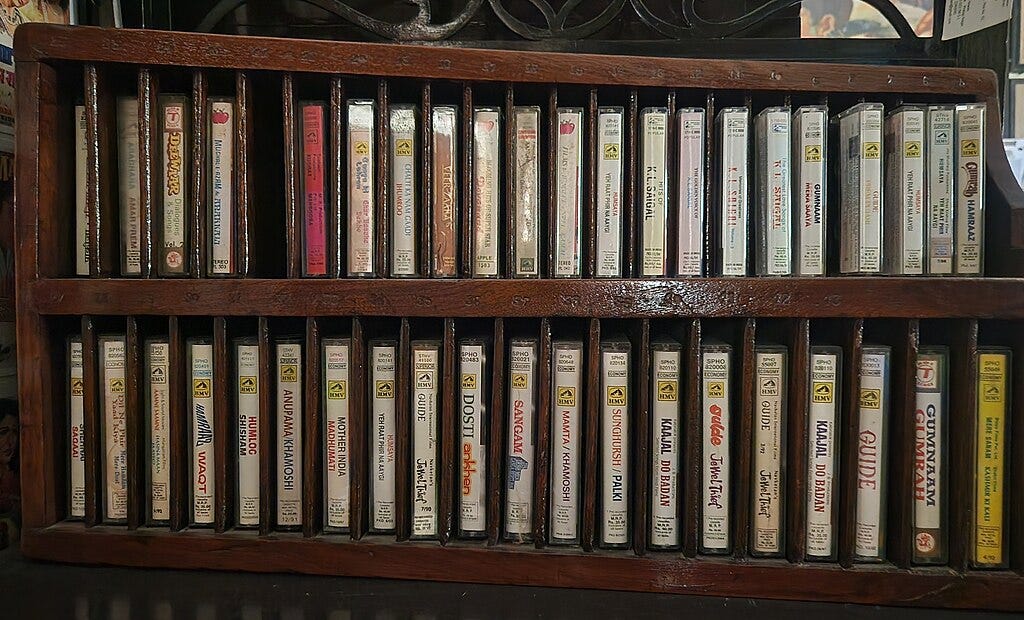

When I think of cassette tapes, a flood of memories comes back—trying to screw the black tape back in with a small finger when my little siblings had pulled them out; a childhood fairytale with the recurring theme of one teaspoonful of cheese; L. Frank Baum’s The Patchwork Girl, which comes back to me like a drug dream (that book is so weird). I’m still addicted to audio, to listening to words that stream in through headphones, just like I’ve always been addicted to words—the words that I used to read on shampoo bottles and now I read on phones, the words that used to flow from my mechanical pencils and now flow on keyboards. Anything short of inserting words directly into my veins—and doing what Ernest Hemingway called “sitting down at a typewriter and opening a vein”—is not enough for me.

We’re approaching the fall, which tends to be a time of nostalgia. The interesting thing about my nostalgia for a childhood self who is obsessed with words is that my current self is exactly the same; she just possesses less mystique. The cassette player makes that story about my word addiction into a charming part of history, perhaps even a prophetic part of history—a personal history about a girl who was just trying to figure out how to live. All that was a long time ago, the story says. And so that time, a long time ago, takes on meaning that it didn’t have then.

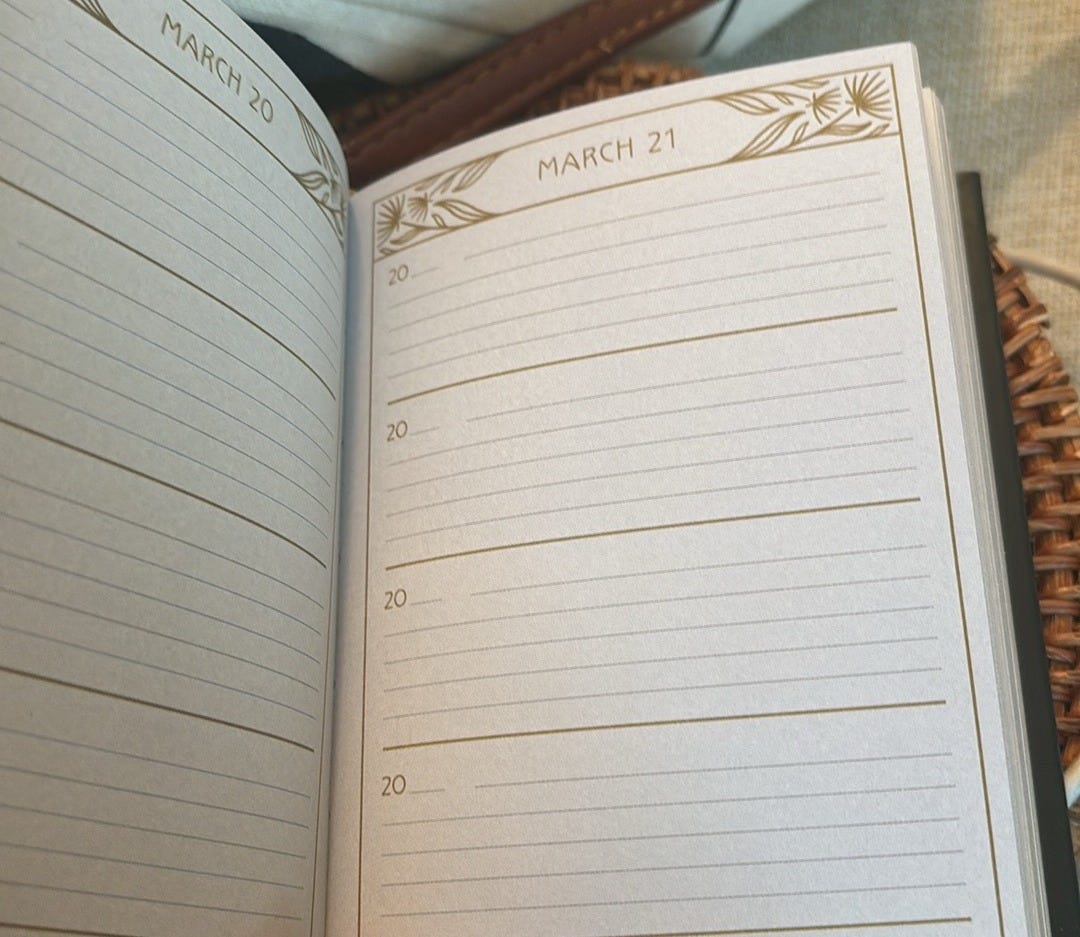

A couple of weeks ago I finally caved on something that has always tempted me and bought one of those one-line-a-day, five-year journals. They’ve always charmed me for reasons I couldn’t describe—I will admit to being tempted by almost every possible version of a fill-in-the-blank notebook—but they struck me as gimmicky and like something I would start but not finish (another feature of my childhood memories is a stack of unfinished notebooks, many of which I do in fact still have).

But when I finally bought one of those journals, I realized that they are kind of a placebo—it matters less whether you actually use it every day of five years and more whether you believe in the idea of the journal, believe in a future version of yourself who will look back on September 19, 2024 in 2025, 2026, and 2029. And this was the reason they held such a fascination for me. The very act of writing something down on a page of a journal with spaces for four more years—I decided to write down the highlight of every day—is a sort of act of faith, a belief that the present is not just any ordinary day but will, in time, become one of those good old days.

I bought the journal because I knew that it would change how I looked at the present by inspiring me to look at it as if it was the past. Fall, with its waves of nostalgia, already inspires this. I can’t embark upon fall without immediately thinking of all the falls that came before, and with them comes the sense that I am living in another future’s memories. One day, we will look back on all these moments, and they will be touching moments of history, like the moment I was listening to cassette tapes at age four.

There’s a cynical way that you could look at the cassette tapes that are all the rage now and the journals that inspire you to historicize your life. There was nothing special about that moment, says the cynic. It’s only special because of the act of looking back. Cassettes were low-fidelity and easily unraveled, and it’s silly that the kids nowadays want cassette tapes of Taylor Swift and Billie Eilish. It’s bad technology, compared to the technology of today. Why not just have a journal, or better, post on Instagram? Why does everything need to be historicized?

But I think people still buy cassette tapes for the same reason that I bought that five-year journal. They want a concrete reminder that they themselves are living in some sort of history—a physical object that draws them back into the physical reality of the moment. All the days that we have now will one day be our histories, and if we are more aware of that, we live them more fully.

Come back next week: to find out why frisbee golf is like The Joe Rogan Experience.

Thanks for your patience: I’m working on another big project that may or may not ever seen the light of day, but it will wrap at the end of September.

One project I can share: I’m writing as a guide over at Read With Me. If you’d like to join us in reading The Secret Garden or pick up A Little Princess, both books are free, with my commentary, in their app!